Isanti Spirits was inspired by the reckless heart and punk rock soul of Rick Schneider. A consummate maker and tinkerer, he constantly has his hands in something creative. A punk rock musician in the 80’s, Rick played the famed Minneapolis club 7th Street Entry at seventeen. He transformed his creative passion for pounding drums to glassblowing in the 90’s and morphed into an art professor. Tastethedram spoke to Rick Schneider and got some really great insight into what makes whisky tick.

Please tell me how the distillery came about? Give us some history about the name.

Please tell me how the distillery came about? Give us some history about the name.

RS: I grew up in a family who drank whiskey and made cocktails for dinner parties. My father and grandfather both preferred Canadian Rye Whiskeys. I am an artist, a glassblower, a musician, a writer, and many other things. For the most part I am simply a maker and a person who loves to learn how to do cool things. I had wanted to learn how to make whiskey since I was in college in Madison Wisconsin in the early 90’s. I was in an early homebrew store there asking about making whiskey and they chuckled at me and reminded me of its illegality. There is no family history or Grandma’s secret recipe to discover in my family. I held the idea in the back of my mind for 20 years. 2008-2012 found me as an art professor in Alabama.

In 2011, I was no longer happy there and was sitting in front of my computer with a glass of Maker’s Mark when the wonder of the internet search for “How to make Whiskey” started me on the path. I found Kent and Don from Dry Fly Distilling and they were willing to talk to me about how to make it happen. I bought a book, read some forums almost every night for a couple of months. I went to my Wife Nikki and said, “What would you say if I wanted to quit teaching and build a whiskey distillery?” Nikki answered simply, “Let’s run the numbers and if you really learn how to do it, let’s go for it!” A stronger finer wife cannot be found. I resigned my teaching position, took a new one teaching glass in Minnesota and started working on the beginnings of Isanti Spirits.

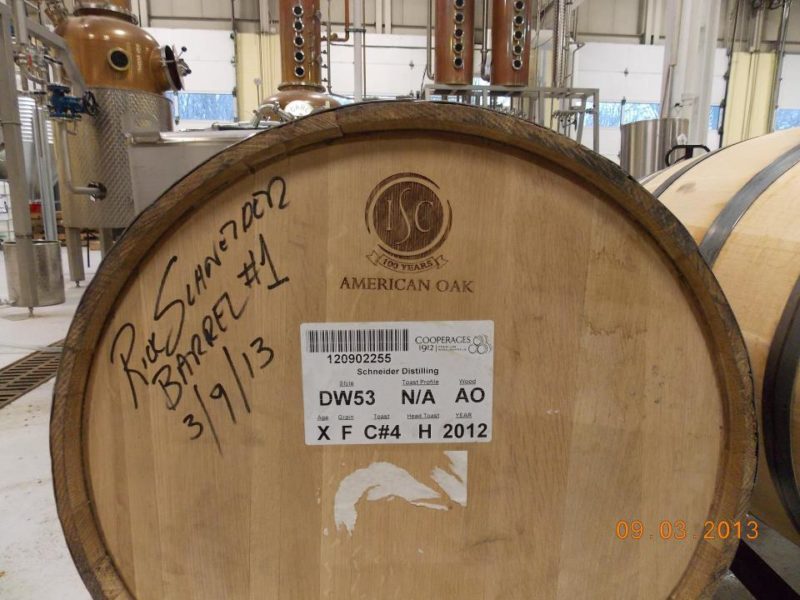

I took a one week class with Dry Fly in 2012 and new I could make this happen, but I wanted to know more. I was the first distiller to take part in a, now defunct, program for craft distillers at Michigan State University. Isanti County is an unlikely place for a distillery. The last dry county in Minnesota, it held out until the late 1960s. Not many thought the county would even consider allowing me to build my distillery here. I found the exact opposite. My neighbors supported me, and they county went to work helping to make it happen.

My distillery is in my back yard. I had to separate my land to make the location fit federal code, and then I spent a year and a half working with the county to create the ordinance allow distilling on a rural property. We started the process in late 2012 and we started distilling on the property 2015.

The name is derived the Santee band of Sioux Indians. It means Knife and the Santee are often referred to as the Knife people. My town and county are both named for them. When I was trying to come up with a name we went with Isanti because so many people around here worked to make my project happen. I get a lot of support from those around me. It is a great sounding word and graphically very fun as it starts and ends with an “I”. I only know of a few words fitting the definition. Illini, Isanti, both Native American tribes, and Illuminati. I’ll leave it to the reader to figure out the meaning if any…..World-wide Whiskey domination maybe?

What have been the main challenges involved in setting up a new distillery? And what has been the part you’ve enjoyed most?

What have been the main challenges involved in setting up a new distillery? And what has been the part you’ve enjoyed most?

RS: Personally, the challenge is waking up every morning with a mountain of doubt and fear weighing on your head. I simply refuse to acknowledge it and keep pushing forward. From a business perspective, it’s getting people to take a chance on and supporting the effort to make something unique and new. It’s getting people to go to a restaurant and break their habits to ask for what I am making. It’s typical for a person to look at drink menu, find something that sounds great or worth a shot and order it. The near impossible task is getting them to say, “hey, any chance you could make your raspberry gin sling with Isanti’s Tilted Cedars Gin?” Therein lies the real challenge.

The part I most enjoy is connecting with people who visit the distillery or who I meet at tasting events. I think my story connects with them and I hope they become a fan.

My then 9yr old son described me as Daring on a school project for starting this distillery, and my daughter continues to tell me I’m the best dad in the world. It can’t get more awesome!

What whiskey expressions do you currently produce, and how are they all different?

What whiskey expressions do you currently produce, and how are they all different?

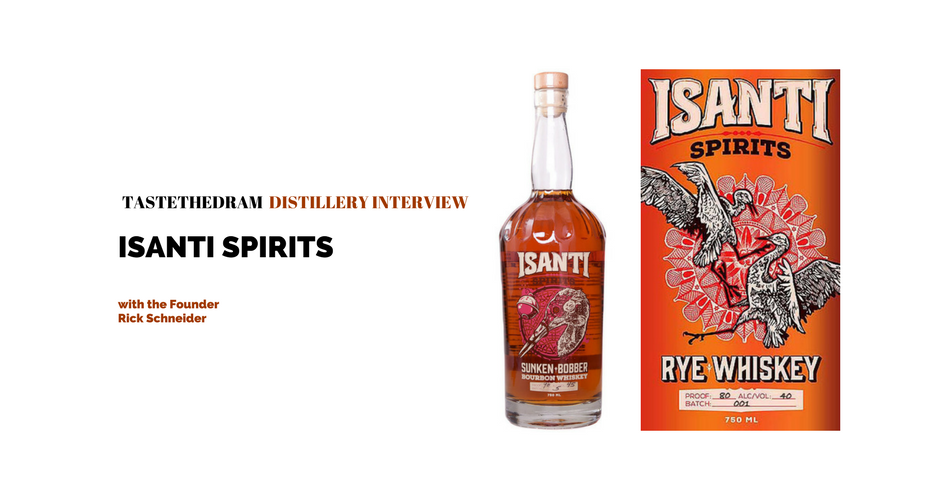

RS: I currently make two whiskeys. Isanti Rye Whiskey and Sunken Bobber Bourbon.

The Isanti Rye Whiskey currently out is 4 years old made by me at Michigan State as my project whiskey. I made 15 barrels at 53 gallons each. I shipped everything I could get from Minnesota so it would taste like what I am making now. I wanted to have an aged big barrel whiskey when we opened. It is heavy on the Caramel and Vanilla, proofed at 86.

Sunken Bobber Bourbon is currently a one year old whiskey made in smaller barrels. I will bottle a 2yr old straight expression in about 4 months. I produce one batch a month in small barrels and the rest in big 53 gallon barrels. I will release a 6yr old in about 4 more years. Sunken Bobber has a rich smoky, hazelnut finish.

I use a few non-traditional grains in my mash bills. They are roasted grains used by brewers. The roasted grains impart unique flavors to each of my whiskeys.

What are you currently doing to stand out in this craft saturated whiskey market?

What are you currently doing to stand out in this craft saturated whiskey market?

RS: I am trying to tell a different story with branding and bold whiskey flavors. I come from a punk rock and creative fine arts background, having played in bands doing all original material when I was a kid. I have an art work, done collaboratively with Nikki, in the Museum of Art and Design in New York. I try to bring a driven creative attitude to what I do. I’ve always lived by the Do what I want and let the chips fall where they may ethos. My wife is a printmaker and designed our bottles with a friend named Justin Kamerer from Kentucky. My wife’s prints have shown all over the world, and Justin does posters for the likes of the Foo Fighters, Metallica, Roger Waters, the Melvins, you name it. Our look is not like anything else on the shelves. I am really working from a basis of word of mouth. I do this all myself with a little help from Nikki and the kids on bottling, so it is hard for me to get out there and sell it.

Why did you start production? Did you see a gap in the market or was it to fulfill some passion?

Why did you start production? Did you see a gap in the market or was it to fulfill some passion?

RS: It is all passion, and a drive to make stuff. I work hard to make a good whiskey with a flavor you can’t find on the shelf. I love every part of making it, except for the record keeping for the feds. Make it or Break, I did it!

Rick, is there a flavor profile that you aim to achieve when malting, mashing, fermenting, distilling and maturing?

Rick, is there a flavor profile that you aim to achieve when malting, mashing, fermenting, distilling and maturing?

RS: I spent a lot of time thinking about what I wanted my flavors to impart to the drinker. The grains I use were picked to enhance every part of it. I don’t malt myself, but I found malts available to push the flavors I wanted to make happen. The Rye Whiskey nailed it. My bourbon ended up having the unexpected smoky character, I believe comes from the roasted grain, and it was better than what I thought I wanted. I started with a good plan and got something even better. Fortunate.

Walk us through the distillation process. From grain to glass? Is there a flavor profile you’re looking for before bottling the whiskey?

Walk us through the distillation process. From grain to glass? Is there a flavor profile you’re looking for before bottling the whiskey?

RS: If you want the whole story you need to visit and hear it in person, but in a nutshell, it goes like this:

I get grain from a fourth-generation farmer, Dale Anderson, who lives a short distance from me and was the surveyor on the land separation mentioned earlier. He grows Minnesota 13 corn and AC Hazelet Rye for me. Minnesota 13 was developed by the University of Minnesota in 1897 and was used in Stearns county to make Minnesota 13 Moonshine during prohibition. It was an early 90-day corn crucial for the short growing season Minnesota climate.

I put 375 gallons of water into a mash vessel with around 1200lbs of milled grain and cook it to 180 degrees Fahrenheit to start gelatinization. It’s like pouring hot water into oatmeal when it gets all sticky. You are making the starch available to conversion into simple sugars. Enzymes then break the starch down into sugars consumable by yeast. At this point it is sweet and Nikki describes the distillery as smelling like caramel cinnamon rolls. If I get the smell right I know I’m heading in the right direction.

Yeast is then added and it converts the sugar into ethanol, CO2, and many other things necessary for the flavor of whiskey. After about 5-6 days I have 500 gallons of Wort at ~13.5%. I distill the wort to strip out the ethanol as fast as possible and get it off the grain. I collect 120 Gallons of Low wines at 40%. The low wines are all the great stuff for whiskey and other less desirable components I need to separate out. The low wines go into my Copper pot still for the spirit run, where I make the separations or cuts. The cuts are broken down into three parts.

The heads (solventy smelling stuff), The hearts (whiskey smelling stuff, where the love is), and the tails (bitter smelling stuff). The hearts are collected in a special tank. I’m looking for a heavy butterscotch caramel kind of smell. It’s quite wonderful if I do say so myself. At that point, I proof to 59% and barrel the whiskey. I spend a lot of my time looking at the barrels and pondering all the reactions and changes happening to create what I will bottle 4, 6, 13 years from now. I use Minnesota barrels made from Minnesota white oak with a level 4 char on the inside.

Do you believe now is the most exciting time for a whiskey lover?

RS: I believe we are close to it. The boom in small scale distilling brought new voices to the industry. Many create fun and invented styles and flavors for whiskey. The best is starting to happen as these producers are finding their whiskeys are now 4 years and older and able to stand up against the known makers. When we are a few more years down the road, we will find ourselves with so many great new whiskeys to enjoy. It’s coming, I think it needs a little more time. Sunken Bobber Bourbon 6yr old in 4 more years. It will happen then.

What are the most important factors affecting whisky distillation? How do you ensure that these are carefully balanced to produce a consistently high-quality product?

What are the most important factors affecting whisky distillation? How do you ensure that these are carefully balanced to produce a consistently high-quality product?

RS: By far the toughest question to answer. I will put it like this. If you put great grain in at the beginning and have a consistent quality process, make the best cuts you can in distillation you can make a great whiskey. A distiller’s nose, understanding of the chemistry involved, and a dedication to ensuring the process is consistent and clean are all crucial. After completing this list, it is up to the consumer to find the flavors and stories they connect with.

What is in the pipeline for 2017 that we should look out for?

RS: I finished my first expansion, a 1200 square foot barrel warehouse. It is freeing up some production space in the original distillery building. Isanti Spirits is now available in Northern Wisconsin, Soon in North Dakota and Chicago. Lofty goals for a one-person operation. This year will see the release of the aforementioned Straight Sunken Bobber Bourbon 2yr old. I tasted it at 16 months and I am very happy with where it is headed. There may be the first distillations of a Minnesota Grape brandy, but it will not get released for at least two years.

Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

RS: Be bold, try new things, break your habits and give the small producers a shot. You hear a lot about local and what it means. To me it is about making your community economy work for you. When you buy a bottle from me or any Minnesota producer 80% of the money stays in Minnesota and supports our jobs and people. When you buy products from out of state, only about 25% of the money stays here. Think about where the money you spend goes. Do you want it to support schools in some other state or the schools right here? We are busting our behinds to make quality whiskeys. It takes time. We need you on our side. Help us get there.