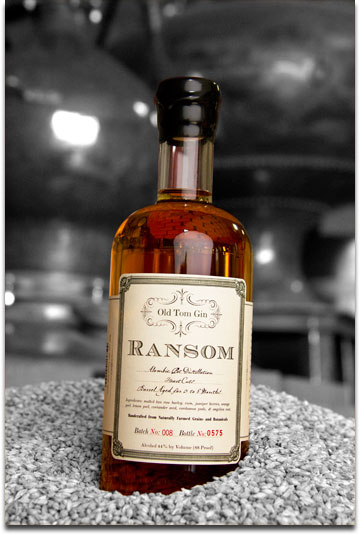

Ransom Spirits was started by Tad Seestedt in 1997 with a small life savings and a fistful of credit cards. The name was chosen to represent the debt incurred to start the business – Tad was paying his own ransom to realize his dream. Initially, the distillery made small amounts of grappa, eau de vie and brandy. Ransom began the production of a number of small-batch fine wines in 1999. In 2007, we took up the craft of grain-based spirits, adding gin, whiskey and vodka to the lineup. In 2010, we combined our crafts of winemaking and distilling to create our first Dry Vermouth.

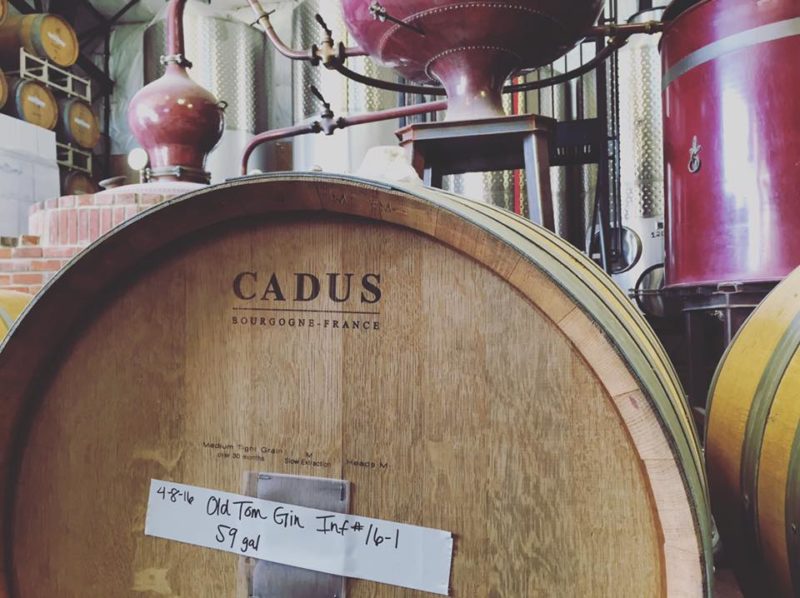

Both the distillery and the winery moved several times in their early days, and in 2008, the purchase of a forty-acre farm outside of Sheridan, Oregon brought them together for the first time. Our first vines were planted in spring 2010, and barley has been planted since 2008. Ransom Farms is located in the Willamette Valley in the foothills of the Coastal Mountain Range, and is home to an abundance of wildlife including cougars, pheasants, and elk. In keeping with our commitment to sustainability and stewardship, our farm has been certified Organic since 2011.

You all are in for a treat. Tad Seestedt knows this industry inside and out, and he shared everything in detail with us, basically he gave us a glimpse at what it takes and how you should look at this industry. We were very fortunate to speak to Ted in detail about the process of spirit distillation.

Tad, tell us about yourself. How did you find yourself immersed in the world of spirit distillation?

Tad, tell us about yourself. How did you find yourself immersed in the world of spirit distillation?

TS: I have been an olfactory driven person since I was a little kid. Second only to the drive of my appetite. Thanks to my parents and from an early age, it was all tied to work. We had a self sufficient farm in Upstate New York, and aside from seafood, and tropical fruits and vegetables, we grew most of what we ate. The raw ingredients were delicious. In between weeding, watering or planting, I would take snack breaks and do things like pluck a carrot out, wash it the creek, or pick a tree ripened apple and have a tasty snack. All of those things have a very particular smell that is directly linked to how good they taste.

As a kid, going to neighbors or friends houses for dinner almost always led to trouble. Opening the oven and sniffing, or sniffing everything on your plate was considered rude. I thought it was a compliment, but also wanted to smell whatever was about to enter my throat before it went down the hatch just to make sure it was safe and/or worthy. That being said, growing up with a five year older brother meant a deficiency in table competition. I learned to eat and enjoy almost everything. My brother would take the breast section of the chickens we raised and ate, while I discovered (and kept secret) that the back had the tastiest parts, especially the two little divots of succulent meat right behind the wing muscle.

What was your vision for the Ransom Distillery? Tell us about the name.

TS: Distillation came to me as an extension of winemaking, and an extension of beverage preference. Sort of a natural progression up the alcohol scale, but also a progression of curiosity. Cocktail culture in the early or mid 80’s when I started going to bars was suffering from a major step backwards. The drinks were nearly all overly sweetened, and the most popular ones had names directly linked to sex, violence and wealth. Not much unlike the pop culture that governs today’s society. Thank Gods, goodness, or something that cocktails and the education of and about, have risen far above the idiocy that dominates our screens and minds today.

I started fooling around with distillation in the early 90’s out of a desire to learn and understand more about how spirits were made (I was working as a winemaker), and what made them taste the way they did. It was immediately addictive. Not in the drinking sense, but in the doing. There is something undeniably magical (although the physics are dead simple) about seeing clear distillate dripping or running out of the end of a condenser tube. I think most distillers would agree.

Name a few other distillers or distilleries who inspire you.

Name a few other distillers or distilleries who inspire you.

TS: The most memorable bottle of spirit that I ever opened was a bottle of apricot aquavitae, made by the Nonino family that a friend carried back from Italy, somewhere in the mid 90’s. The perfume of it pervaded the room anytime that bottle was opened and poured into a glass. It was incredible. Another was a bottle of Mirabelle, that my girlfriend at the time brought back from France. Her stepfather (an accountant) had made it in his garage. I figured that if some white collar French guy could make something that good in his garage, that I could probably do it as well. It took more practice and learning than I had thought. For here in the US, George Rupf and St. George, (and now Lance Winters) have had a very long run of making exceptional spirits across all category lines. The differentiation is that these spirits all have the signature of the raw materials that were made from. That is the holy grail. To take what is fermented, and have the distillate smell and taste like those raw materials is the ultimate challenge.

What whiskey/gin expressions do you currently produce, and how are they all different?

TS: We are doing a few different whiskies, and strive to make all of them in a grain forward manner that emphasizes what the starting points for grain were. One of them, the “Emerald” whiskey was an attempt to remake a whiskey that could possibly smell and taste like whiskies made in Ireland in the mid 1800’s or earlier (we cannot use the term “Irish Whiskey” and have been threatened by the Irish Whiskey Association against having that term used anywhere in our website or educational material). Dave Wondrich, an old friend of mine from before either one of us entered into the professional spirits world, was doing research into whiskies made in Ireland and came across a series of actual mash bills used by an Irish Distillery in the early and mid 1800’s. They all contained oats as a major component.

Oats ceased being a component of whiskies made on the Emerald Isle sometime around the turn of the century. The 20th century. There were hearings held in England in the early 1900’s to determine what could be called an “Irish Whiskey” (that term is now trademarked) and what could not. The Powers and Jameson families testified that as long as they had been making whiskey that oats had been present in the mash bill. Further that without oats the whiskey could not be genuinely linked to the Emerald Island. My point is that each grain in its own percentage can have an enormous impact on what that spirit smells and tastes like. We don’t really focus on that in this country, or maybe even in the whiskey world as a whole, and it is unfortunate.

Marketing has ruled American taste and preferences for far too long, and the myth, smoke and mirrors ( some may simply call it bullshit) have steered the consumer, the industry professional, and yes even the media, in the direction that the marketing department wanted to drive people towards. There is way too much talk about things, and terms thrown about, that really mean nothing. Small batch, single barrel, single grain, some kind of barrel finished….. on and on. What really matters is not discussed, or it is passed off as a “proprietary secret”. From my perspective there are only two reasons to keep secrets, one because there is something to hide, and two because there is nothing to tell. Those secrets exact a huge disservice upon the consumer and the industry as a whole. “Secret” is quite simply a trite euphemism for bullshit. When you hear that term, take a good sniff and decide for yourself.

What really matters is the raw ingredients, how they were fermented, how they were distilled, maybe what kind of still, how the cuts were made, which of the cuts went into barrel, what kind of barrels were used throughout the aging process, which of the barrels were selected for a blend, and how carefully they were selected for a blend. New cooperage, used cooperage, charred or toasted, if the barrels were used were they cleaned or not before filling? The details are endless. The problem is that the details of the details are way too complicated and very few people have the interest or patience in hearing them, nor have the patience to analyze (or train their palates) everything they taste.

All of that being said, we are entering another era of consumerism, where the norm is a much higher sense of awareness than was prevalent in the past. It is a good thing. I suppose that as producers and distillers we are opened up to an entirely new set and level of questions (and sometimes interrogation) but in the end it is mostly good. So long as there is knowledge and true curiosity behind the questions, and not an inquisition based upon ideology that is short of understanding, knowledge and tolerance. We as producers bear a heavy responsibility to be open, and sincerely interested in education. It is unavoidable that some of those asking the questions may have more in common with Tomas de Torquemada, than Einstein, but such contrast in unavoidable.

Why did you start production? Did you see a gap in the market or was it to fulfill some passion?

Why did you start production? Did you see a gap in the market or was it to fulfill some passion?

TS: I started my distillery because I was smitten with the concepts of fermentation and distillation and how those two walked hand in hand. My comprehension of market considerations was negligible. The distillery hemorrhaged money for the first seven years. I did not have the best business plan, or business mind, although I do now understand that somehow the bills need to get paid. My other half maintained without (too much) complaint my 200 pound frame for all of those seven years. A testimony to devotion, caring and friendship. Now, in the 20th year of Ransom Spirits, I can finally afford to buy my own groceries.

What exactly does your job entail?

TS: My job now entails far too much time dealing with the tertiary elements of running a distillery. Compliance, regulations, sales, distributor relations, general management, incessant communication and re-communication and a relentless avalanche of emails. Sometimes I distill, occasionally I ferment and at times I ride the tractor. I advise everyone I like to not start a business and to keep a good job if they have it. All of the jokes aside, there are plenty of moments when the true reasons for starting a distillery strike home and penetrate the fog of stress. It can be as simple as hosing off the floor after cleaning a fermenter, hoses or pump. Sometimes when being knowingly late for dinner, to sneak a taste of a ferment or whiskey/gin barrel and to savor that moment is the best. Questioning all the years of knowledge and experience in the space of five minutes, and wondering if your snap judgment is sharper than the sum of the years is constantly reinvigorating. We never really know for sure, and anyone who claims to know everything is either delusional, completely full of shit or a combo of the two.

What are the maturation conditions like?

What are the maturation conditions like?

TS: We mature in a place (Oregon) that is a rain forest for 7 or 8 months out of the year and a desert for the remainder. There is a definite shift in how our summer aged gins age compared to our winter aged gins, and I like that. With the whiskies because they are aged over a period of years, the difference is less apparent. I strongly prefer used, toasted wood that does not interfere much with the signature of the raw ingredients but does lend some influence, wood sugars, oxidation and integration to the spirits.

What have been the main challenges involved in setting up a new distillery?

TS: The main challenges are over for us. We will celebrate our 20th anniversary this year, and things are generally good. Changes in the market and changes in the distribution system that are hostile to small distilleries probably pose the greatest challenge at this point. In the early stages, finances were the main challenge. Without investors and unable to secure a commercial bank loan it was incredibly difficult. Also, the time necessary to find, research and perfect the appropriate products is uncomfortably long if you want to do it right. The pressure to sell in enormous and undeniable. Luckily for me, I had zero business sense when I started my distillery, and thought that worrying about money was not for “artisans”. That sense got slapped into my head at some point, maybe when I realized that buying groceries for years with a credit card would eventually have seriously negative impacts.

Where or who do you feel is the driving, innovative force behind our craft distilling industry right now?

Where or who do you feel is the driving, innovative force behind our craft distilling industry right now?

TS: The driving force behind the industry now and for the last ten years has been the people behind the bar, and the people in front of it as well. Our prayers have been answered! Not that the marketing dept don’t have influence, because they certainly do, but it is tempered by people who have minds and taste buds of their own. They encourage producers to push towards higher quality and to also push the limits of what we think is normal. The spectrum of what is possible is galaxy sized or larger.

For quite sometime now, American whiskey has taken off, what with the expanding number of artisan distilleries and the return of rye to popularity. What’s behind the boom?

For quite sometime now, American whiskey has taken off, what with the expanding number of artisan distilleries and the return of rye to popularity. What’s behind the boom?

TS: Rye was the original American whiskey. Not to downplay Bourbon because that is now what the US is known for, but if we go back further in time Rye was the “king” of America. I think that also the consumer wants to expand horizons, and that is nothing but good. We are currently at about 60 degrees with 300 left to look at. The possibilities for American whiskey are nearly endless. We are hopefully just beginning to scratch the surface. If the boom for whiskey is linked to the decline of vodka, it is probably a positive thing. Nothing in particular against Vodka, but life is all too short. The more flavor the better.

What attributes would you say are most important for a master distiller to possess?

TS: The term “master distiller” is thrown about so loosely it makes me never want to use or have that term used upon me or anyone else. Unless that person is over 60 years old and has no less than 30 years of experience. The spirits boom and the power of the internet have created an environment in which “instant experts” have multiplied faster than caged rabbits. I remember going to distillery conventions five to ten years ago and seeing way too many people wearing shirts with the title of “master distiller” emblazoned upon their chests. It was such a turn off, and an obvious ego trip on their parts. I knew for a fact that most of them had only been running stills for two or three years. Far from being masters of whatever it was they thought they were. Humility however, runs short in this industry on all ends of it. The attributes would be a function of time, understanding, humility, curiosity, and ability. None of which can be mastered without a lot of hours being logged.

What’s the secret to a great dram?

TS: The secret to a great dram is a combination of the dram itself, the person drinking it, and the other people who are also drinking. Although it is quite possible to have the perfect dram by oneself. It is really the appreciation that makes the difference. And it does help to have something very tasty to help that along. In my opinion it would have to be neat, and also have to sipped on in tiny sips that draw the process out for as long as possible.

Is there a right way to drink whiskey?

TS: The right way to do anything, is to do it in the manner that feels right. I might be snobby in thinking that only drinking neat is how it should be done, and that the distiller choose the right proof at which that particular mash bill or blend was bottled. But that negates the concept that we all have different preferences and therein lies the beauty of our palate likes or dislikes. It is the diversity that makes it all worthwhile, and all the more enjoyable.

What – in your opinion – makes the spirits produced at your distillery unique?

What – in your opinion – makes the spirits produced at your distillery unique?

TS: At Ransom we focus primarily on our raw ingredients, their quality and how we can make that quality shine in the finished product. It is less about the other impacts on flavor and aromatic profiles. Wood is the big one. We want the barrel to be primarily an aging vessel that imparts a degree of complexity and depth. We do not want it to dominate what we put in the bottle. If our discussion leads to mush into cooperage, we have gone astray. We want to talk about grains, botanicals, ferments, which cuts were made, and then barrels, aging and blending. It is not a style for everyone. I have a dumb allegory that I like to use in reference to wood, and it is using dry aged steak as the subject. If you have a delicious dry aged steak, would you douse it with ketchup and steak sauce, or dab it with a little salt and pepper so you can actually taste the steak? New wood is like ketchup and steak sauce, it covers up whatever you raw ingredient was, and makes it all taste uniform. Not bad on a burger, but on a dry aged steak you just wasted both your time and your money. We put dry aged steak in barrels, and want to avoid ketchup getting anywhere close.

What are your hopes for the distillery 5 years from now? What do you want to be known for?

What are your hopes for the distillery 5 years from now? What do you want to be known for?

TS: 5 years from now seems like a long time, but in this industry what we do while we are living may only be experienced and tasted by others after we are dead and gone. Even more true for the older ones in the business or the older ones getting into the business. At 52 years old, I can look at and begin long term projects but it takes longer than I have left to figure things out. So many variables, and so many years required to evaluate. Maybe that is where the “master distiller” comes in. A real master, would have to have apprenticed to a master, and have decades of different experiments to taste and consider and to also do that over the course of decades. And more importantly, have a real master to talk to about it all. Where are those guys?